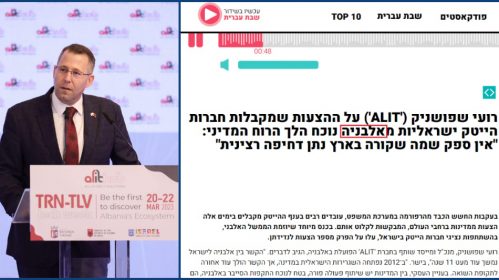

Rabbi Yisroel Finman “We Need to Pay the Albanian People Back

Like many immigrants to Albania, Rabbi Yisroel Finman came here by accident, but then found himself inexplicably drawn to the country, and with no desire to leave.

Like many immigrants to Albania, Rabbi Yisroel Finman came here by accident, but then found himself inexplicably drawn to the country, and with no desire to leave.

Having tried to get a residence permit in Greece to work with a kosher certification organization, he travelled to Albania with the intention of remaining there for the short term. Fast forward many years and he is staying put and has big plans for his time here.

Ndiq "Izraeli Biznes" në Facebook dhe Twitter dhe Instagram dhe behu anetar i Grupit Izraeli dhe Shqiptaret

“I really feel the finger of God here. That is why I believe I couldn’t get a residence permit in Greece. A whole chain of events occurred which brought new ideas and doors that seemed to open one after another,” he explains.

“Things happen for a reason. We all have missions in life and everyone’s soul has things to do. The body is only here to do what the soul wants us to do. This is how I feel about Albania. I am still trying to figure out my connection to this country, rather than over-analyzing I believe in following my instincts, often just following the tip of my nose into the unknown.”

In 2012, he spent a month in Saloniki, meeting with companies and hotels and saw the potential for developing Israeli and kosher foods for export. Noting the potential for international exports for the kosher market, as well as developing Israeli tourism to Greece, the Rabbi was living in Greece and working with Balkan Kosher, a newly established kosher food certification agency and connecting with Israeli travel agencies.

He travelled back and forth from the United States to Greece and travelled throughout the Balkans looking at possibilities. As the business grew, he realised he had to be there more but was unable to navigate the red tape to secure his permit.

At that point, he figured it was better to be somewhere else, so he went to Albania. He feels that this is where he was meant to be and describes how he enjoys wandering the streets, smelling the history, going to places that are not even on the map, and loving every minute of it. Of course, the hospitality of Albanians was a big plus as well.

“People in the Balkans may hate each other but they are very friendly to foreigners. Each time I went to Albania, people would see my kippah and exclaim “Ahh Israel! Let me buy you a coffee”.”

He explained that in the first two years of being here, it was impossible to buy a cup of coffee for himself or for anyone else. The rabbi came to respect the Albanian way of welcoming guests.

During one of these impromptu coffee dates in Shkodra, a new-found friend disappeared into the back of the coffee shop, promising to return. After some time, the Rabbi became nervous, wondering what was in store for him. After 15 minutes, his host returned and presented him with a yellow piece of a newspaper featuring a photo of three women. He explained that one was his grandmother and the other was a Jewish woman who lived in their house during WWII.

This was not the first time he heard stories like this. As news spread that there was a Rabbi in Albania, people would stop him on the streets and even message him on social media to tell them snippets of information about their links with the Jewish community.

During a trip to Himare, he met a young man who was fixing the air conditioning in a hotel. He introduced himself as Moise. This is not an Albanian name, or a Turkish name, it is a Ladino variation of the Jewish name Moses, the Rabbi explains.

He asked him “where did you get this name?” but the young man didn’t know anything other than he was named after his grandfather who was in turn, named after his.

“This is a Jewish tradition, the Rabbi said, “your family has Jewish roots.”

On another occasion over coffee in Vlore, a man approached him and told him that there used to be a lot of Jews in the area. He also told the Rabbi about a type of fruit that used to be grown in the area for export to Palestine and Italy. The man described it as “jew fruit” and being similar to an orange or lemon.

After a bit of research, the Rabbi deduced he was referring to etrog- a fruit used in Jewish rituals on the Sukkot holiday.

“The more I research, the more I understand that a lot more needs to be uncovered,” he said.

Historians he has spoken to over the years have all agreed that Albania has a lot of Jewish history with many areas at some time being Jewish or having a Jewish community. During the 18th Century, he said, there was a massive conversion to Islam from Judaism and Christianity.

“Look at 1600 years ago in Sarande- there is a synagogue from the 4th century. That whole area up to Vlora has Jewish history. Ioannina has had a Jewish community for 2000 years, why wouldn’t Albania have one as well?” he said.

“There is a strong history of Jews in the Balkans. After the Romans invaded Israel, hundreds of thousands of Jews were transported to Italy and the Balkans as slaves.”

One historian even told the Rabbi that in the national library of Istanbul is a book dating from the 18th Century. Written by an Ottoman, it provides a detailed account of Jewish history in Albania.

“We know there was a Jewish presence but we don’t know how much. We need to find someone who can understand 17th and 18th Century Turkish!”

Today, the Rabbi spends a lot of time trying to find out more. Working with Kutjim Cashku, the Rector of the Marubi Film School they are creating an oral archive by interviewing families who took in Jews, or those that were saved by Albanians.

The Rabbi explained that during WWII, not a single jew in the country was killed by the Nazis. Instead, Albanian families of all cultural and religious

backgrounds took jews in and “kept their mouths shut” while being aware that by doing so, they risked the lives of the whole community.

“They risked everything to save strangers,” he said. “This is truly remarkable.”

Following the media attention on the Solomon Museum in Berat the Rabbi got thinking about how else to preserve and promote this extraordinary history. His idea was to open a small museum in Tirana, something that would represent the whole country.

With enough materials to take up some 400sqm, he believes tourists will flock. But his ideas go further than that.

“I am creating a centre called Besa&Shalom- besa defines Albanian people, shalom defines Jews. I want to bring Albanians and Jews together. We have much to teach one another. I want to reach out to the international community to show them how beautiful Albania and the story is.”

The centre would have a Jewish library translated into Albanian, and offer meetings and events. It would also provide education, support, and wide-ranging initiatives to help Albania.

“The Albanians saved my people. I want us to pay them back.”

The Rabbi goes on to talk about the issue of mass emigration. He explains it’s not sustainable and the countries agricultural industry will fail as no one wants to work in it and it is too expensive to efficiently modernise.

He is concerned that Albanians will continue to leave, private companies will buy up the land and import cheap foreign labour to work the land.

“This is unacceptable”, he said, “It’s my mission to help the Albanian people.”

His plan to help comes in many forms. Explaining that the education system feeds into the job market, he says he wants to utilise technology, big data, and social media analytics to find out what people really want and what can be done to provide a better future for them.

“By analysing this data, we can figure out what will work, what Albanians would like to have and then we can provide the education needed to achieve that,” he explains.

Through data mining and analysis, he would hope to ascertain what industries people want to work in locally. Then, with the help of international partners, he would like to offer courses, education and qualifications in these fields. In addition to this, investment from foreign companies and businesses is key.

“There is only so much Israel can do to help. It’s a small country. They do help much more than people are aware. Much of what Israel does in other countries is done clandestinely. I am reaching out to the International Jewish community to say what I see and to encourage investments through philanthropy and business. We need to assist the Albanian people and we must make sure it will help the Albanian people in the right way.” the Rabbi said.

Lastly, our conversation turns towards women’s rights.

“I don’t know if I would describe myself as a feminist because I am not sure what that really means, but misogyny has always bothered me,” he said.

Growing up in a single-parent household with his mother and sisters, the Rabbi explains his sensitivity towards women and the struggles they face. He then quotes the Torah and the Jewish belief that Eve was purposely created from Adam’s side so that they would be equal partners in all aspects of life.

“Everything we are doing in our lives is with the aim of returning to the Garden of Eden. Paradise can never be achieved until men and women are equal at home, in society and in the world at large.”

He was also the first Orthodox Rabbi to fight against domestic violence in America. When he was in his 40s, the Jewish Federation of New York put together a core group of mostly social workers to target domestic violence in the Jewish community.

Working with a Conservative Rabbi and a Reformed Rabbi, they set about writing a manual that was sent to all Rabbis in America, to enable them in recognising signs of domestic violence and how to support those suffering with it in the community. While it took some years for the community to come out of denial, he believes his work had a valuable impact.

Another plan that the Rabbi has lined up is W.E.W., Women Empowering Women, an organization in Albania that centres around facilitating a mentoring programme for local women. By gathering women from different backgrounds, careers, and walks of life, and teaming them up with younger women, a support network can be created. He hopes this will help eliminate some feelings of apathy in society, and again, reduce the startlingly high figures related to emigration.

As our conversation draws to a close, he explains to me once again;

“There is something very curious about the connection between Albanian Nation and the Jewish Nation. It’s not just that Albania wants our help, its that there seems to be a unique, soul affinity between the two peoples. There is a buried connection here, we need to unearth it- we need to pay the Albanian people back.”